As John Kingdon put it: “Speculations on the origins of bipedalism are often fascinating exhibitions of ingenuity – expressing above all, that this is a theater for intellectual daring.” Many books and scientific papers have been published in the literature outlining the author’s own “unique and brilliant” idea on the matter. Often, but surprisingly not always, the author will start with a review of some other ideas on the subject. In doing so, however, this almost always seems to be done merely in order to set up a series of straw men, that can then be knocked down triumphantly as the author reveals the genius of his/her idea which is, of course, the best of all.

I did an extensive literature review for my PhD and found at least 41 published ideas on hominin bipedal origins. Many of them started with some kind of brief audit of other models but none were comprehensive. Even Rose’s (1991) excellent summary of ideas missed a few and, of course, some new ones have been published since. Usually, there is no indication of the selection criteria used to determine which ideas have been included in the review and why others were omitted and there is never any attempt to evaluate the models objectively before the author’s own pet theory is rolled out.

This has always seemed odd to me, as academic careers are all judged on the quality of one’s written material and as one progresses through school and university, one quickly learns that the very currency of success is determined by what others think of your work. Anyone who has had to mark a student exam, or a an essay, will know that the method employed to do so is to come up with a marking “rubric” – where a kind of “ideal” answer is sketched out – so that the student’s work can be assessed in comparison to that, quite high, bar.

Often one gets to know how subjective this process often is – even though it is not supposed to be. Of the three referees of my PhD thesis, one thought it excellent and marked it for an immediate pass, one thought is was good, but with some amendments and a third failed it outright, claiming that I was stealing his ideas (even though he was already the fourth most cited author in the thesis and I went out of my way to praise his work at every opportunity.)

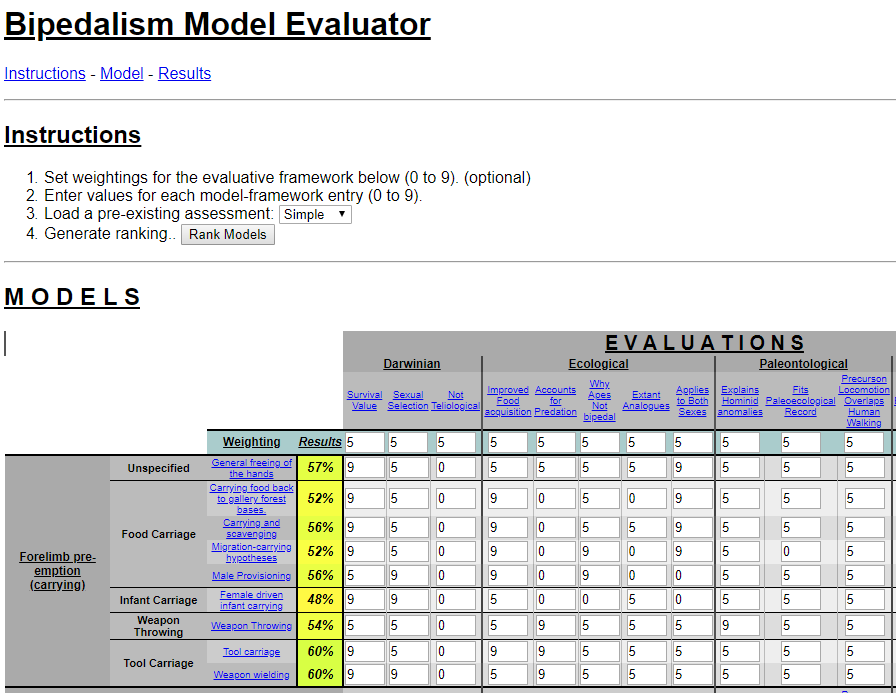

With this in mind, I decided to try to design an evaluative framework of models of bipedal origin – the kind of marking rubric that anyone working in academia would be familiar with. Although this in itself is quite subjective, I tried to come up with a set of criteria that a “perfect” model of hominin bipedal origins should meet and then tried to assess all the models against that rubric.

To make this as transparent as possible, I got my software guru son to design an on-line version of the evaluator on line so anyone interested can read my assessments themselves, criticise them and put in their own assessments. If they don’t agree with my criteria, they can weight them accordingly (giving them a weighting of zero if they think it should be omitted completely). I put this up around 2015 but I have not had a single response. Oh well, you can only do one’s best.

Here’s a link to the evalutator. Please try it for yourself… I challenge you to come up with an assessment that shows the wading hypothesis to be one of the weaker models.

Kingdon, J. (2003). Lowly Origins. Princeton University Press (Woodstock)

Rose, M. (1991). The Process of Bipedalization in Hominids. In: Senut, B., Coppens Y; (Eds) Origine(s) de la bipedie chez les hominides. In: Coppens, Y., Senut, B. (eds.), (1991). Origine(s) de la bipedalie chez les hominides. CNRS (Paris)